In Argentina, Thanksgiving is just another Thursday. They don’t have hokey stories about colonial invaders baking a casserole for indigenous people. They don’t feel compelled to travel long distances to overeat with relatives and watch football on television. And they certainly don’t serve roasted turkey.

I’ve never enjoyed Thanksgiving. It’s not tied to any bad experience; I just never understood it. Even as a child, I found the whole production confusing. Growing up in the American south we ate delicious fried chicken all the time. Being forced to eat a plate of dry turkey once a year felt like punishment.

After decades of disappointing friends and family with my lack of enthusiasm, I decided to step aside and let them enjoy their Thursday without me.

This year I spent the holiday in Buenos Aires. I had business there the following week. I thought it would be a great place to avoid the American celebration. It’s also home to my favorite steakhouse, Parrilla Pena.

“Parrilla” translates to grill. It’s the local word for a place that serves meat. That pile of cut lemons shown on the counter is the closest thing they have to a vegetarian meal option.

Pena in this case is the street, Rodriguez Pena. It’s off the main drag. My local friends never want to join me at Parrilla Pena. It’s not fancy enough for them. But it’s been my favorite place to eat in Buenos Aires since I found it by accident almost ten years ago.

The Perfect Thanksgiving Lunch

The first time I ate at Parrilla Pena I fell in love. The food is great, and the place runs like a well-oiled machine.

When you walk in the boss tells you to choose a seat and sit down. Within 30-seconds a sharp-dressed waiter turns up to offer you a drink. Another 30-seconds and you’ve got a house-made beef empanada in front of you. It’s their version of amuse-bouche.

Now, the waiter wants your order. You have the entire cow to choose from. They make sausages out of the parts that don’t grill well. If you decide to visit, my recommended order for two people is:

· Provoleta (a grilled slab of provolone cheese)

· ½ Bife de Lomo (a huge beef tenderloin filet)

· Pappas Fritas (fries)

· Helado Dulce de Leche Granizado (classic Argentine ice cream w/chocolate flakes)

Personally, I skip the provoleta, but if you haven’t had it, it’s a must try.

The first time I had this feast was about ten years ago. Excluding the slab of grilled cheese, I had it again for Thanksgiving lunch this year. However, I had an important choice when it came time to pay the bill.

Don’t Use Your Credit Card

Earlier that morning my local friend Alex reminded me, “Don’t use your credit card!” I almost forgot how things work down here. Using a card means I’d be subject to the official exchange rate, which masks radical inflation.

The difference between card and cash is tremendous. It’s the equivalent of doubling or tripling your buying power. This uniquely Argentine way of paying for things turns everyone into a currency trader.

The total cost of my Thanksgiving lunch was $21,000 pesos. The local money situation is out of control. That same meal costs $22,000 one week later.

Argentina runs inflation of roughly ½ % per day. The current estimate is…around ~150% per year.

While that might sound extreme, here’s what it looks like as a customer at Parrilla Pena who orders the same thing every time.

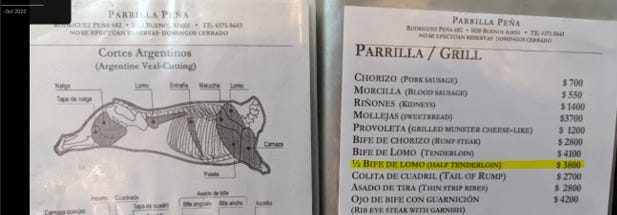

Notice the first menu shows a date of 2019. The ½ Bife de Lomo is $810.

The second menu dated October 2022 shows the same item priced at $3,800. That’s around ~370% higher in two years.

The next menu is from my visit two weeks ago. The same size and cut of meat, prepared the same way, was $12,900.

On Tuesday of this week, less than two weeks after my visit, the ½ Bife De Lomo costs $13,500.

Visit next week and it’ll likely cost you more than $14,000…for the exact same steak.

The only thing that changes is how many pesos you need to pay for lunch.

It’s Starting to Look Like Havana

People ask me all the time, “What’s your favorite city?” It’s always been Buenos Aires.

Forgetting about the money issues, there’s something magical about the place. It feels like how I’d imagine Paris in the ‘20s...except with a bunch of Italian-looking people running around speaking Spanish. They eat dinner at 10:00 PM, play polo, and look down their noses at the rest of South America. I don’t know many places with that type of character.

But living with unstable money takes a toll on people. The city looks tired. The glossy oil-painted doors, polished brass gates, and stylish mid-century lobbies of the apartments in Recoleta don’t shine quite as bright as they once did.

When I arrived at my hotel the staff looked tired, weathered, frayed around the edges. The desk clerk went into his pitch of how many hundreds of thousands of pesos I’d need to pay in with cash. I had the pesos….and he had a way to count them.

The “Official Rate”

On my first visit, almost ten years ago, a Raymond James analyst on the trip with me explained the system.

He asked me, “You brought a bunch of dollars, right?” That first trip, I didn’t. I had the usual ~$1,000 USD and a few euros.

He told me the expensive hotel we stayed in charged our credit cards at the “official rate.” If we had cash, we’d get the “blue rate.” But he had a guy who’d get us an even better rate. The “guy” came by on a moped at night and did the cash swap out of his backpack. If nothing less, it sounded fun.

Back then, the “official rate” was 8:1. That means the hotel charge of $4,000 (pesos) per night meant we’d pay USD$500 using our credit card.

If we had cash, we’d get the blue rate. That’s 12:1. It means the nightly hotel charge of $4,000 per night converted to USD$333. But the guy on the moped offered 16:1. That meant we’d only pay USD$250...for the exact same hotel room.

That was then. On my trip last week, the same three rates were around 40-times higher:

· Official rate used by credit cards 350:1

· Cash rate 900:1

· “Guy on moped” rate ~1,200:1

Meanwhile, leftover pesos from my last trip are worthless. I almost always have enough local currency to get a taxi from the airport to my hotel anywhere in the world. It’s a traveler instinct, and an old habit.

$800 pesos was more than enough for a ride from the airport and a steak at Parrilla Pena on my first trip. Now it doesn’t buy a cup of coffee.

When Things Fall Apart

Argentina just elected a new president, Javier Milei. He appears to be a libertarian agent of change. At lunch in Buenos Aires my local friends told me he’s a total outsider. While it looks like a good change, they say it’s too late. International investors have had enough of the Argentine value trap.

I remember the last agent of change, Mauricio Macri. In early 2015 he spoke at a conference I attended. He explained his business background, plans for reform, and gave a sense of optimism. Nothing changed.

It’s fashionable to bet on Argentine stocks right now. People go on and on about the value, the turnaround, the years of gains ahead if the country reforms. American investors love that kind of bet. It’s the Powerball syndrome… nobody reads the odds printed on the back of the ticket.

Instead of betting on unlikely outcomes, betting on human nature has better odds. People tend to keep doing things until they can’t. They only change because they have to, not because they want to.

Change means hard work, and sacrifice. A true rock bottom only happens when they’re out of options.

The money problems in Argentina are extreme, but not unique. Most people there realize what caused it. I heard a hotel clerk tell a British tourist, “We kept spending money we didn’t have.”

It’s a worldwide phenomenon. Humans, undisciplined by nature, always opt for buy-now, pay-later. And nobody loves buying on credit more than the U.S.

The 21st century is a time of peak borrowing capacity for humans. There’s no period I know of in history where buy-now, pay-later worked so well. We’re almost a quarter of the way through the century and so far, no consequences. Instead, the profligate profit and the disciplined get left behind. But it can’t last. At some point, the game breaks down.

Rising prices never come back down. While the cost of my favorite meal at Parrilla Pena goes up by 1% every two days, U.S. inflation moves up at a slower pace. Neither returns to the old price. The dime store turns into the dollar store, then the $10 store, and eventually $100.

The old 100-peso notes bought a nice lunch on my first trip. Now worth less than a dime, my kids use them as play money.

While Argentine inflation is shocking, U.S. inflation might be more dangerous. At least the Argentine people know what’s happening, conceptionally. Outside of speculating, Americans don’t seem to grasp any economic concepts. Maybe Lenin was right, the capitalist will try to profit from the sale of rope later used to hang him.

It’s All Paper in The End

Once you see the money game for what it is, you can’t unsee it. In fact, you can’t see anything else.

Capitalism is an idea from last century. It worked well, but it made the system difficult to control. And control freaks don’t like that.

The free-market experiment goes down as peak freedom for the individual. You owned your output. What you didn’t spend became capital. Capital was a tool you could loan to a business in need. When successful, that returned a multiple of the initial principal.

Those days are over. What we have now is centrally-controlled economics. Every day we pant like dogs waiting for a Federal Reserve representative to tell us what kind of market we have. It’s peak madness, if you can see it. But people can’t see it.

The smart Argentinos hide money in dollars, and real estate. The country’s rigorous capital controls mean they can’t easily move money in and out without losing most of it. Just like in paying the bill for my Thanksgiving feast, they face a complex, tiered exchange system. Hiding in real estate tends to be their best be.

Hiding, protecting, and preserving aren’t on the minds of Americans. They want speculative excitement, growth, radical innovation… and they’ll risk it all to get it.

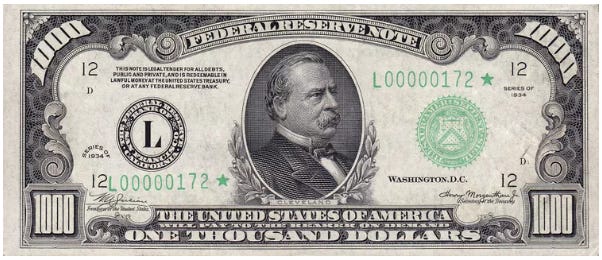

Meanwhile, the largest U.S. currency note is $100. Until 1969 there was a $1,000 bill in circulation. Gold had a fixed price of $35/oz back then. That means a $1,000 bill bought ~28.5 ounces of gold worth $58,000 today.

Grover Cleveland looks distinguished on that $1,000 bill. It’s a lot more impressive than the giant stacks of 1,000 peso notes I carried away from the off-market change house in Buenos Aires. Those have a bird on them, my guess is no person wanted to loan their picture.

You Either Have It Or You Don’t

While the Argentine wealthy class hides in property, Americans don’t hide at all.

Shockingly, you can still buy physical gold in the U.S. Nobody wants it. Truly, nobody.

At the bottom of the Trustee Portfolio I list the contact information for one of the gold dealers I use. I called him after I got back from Argentina. He sounded like the Maytag repair man. Nobody wants gold. I bet the Argentinos wouldn’t mind having a few coins held over from a former era.

Gold holds up, period. These two charts show what a quarter century of monetary excess looks like. First, the total value of U.S. Treasury debt held publicly. The data only goes back to 2005. Since that time, the debt pile is 335% larger.

It looks eerily similar to the explosive chart of the Argentine peso. People say it can never happen here...but it already is…at a slower pace.

Americans can hide in real estate. It’s not the worst idea. But it already saw its day. Plus, it costs money to maintain. Taxes, insurance, repairs, and for some, interest payments, all mean real money out the door every year. That eats into the benefits of hiding.

Meanwhile, gold just sits. It does nothing, and an Argentino might tell you that’s a good thing.

The few Americans who are interested in gold want to trade it. It’s a mistake. You either own it or you don’t.

An Argentino with a call option on gold ten years ago didn’t hold up as well as one with a stack of coins.

Get the gold while you can… and remember, not everything is a gamble to multiply your money. You’re already rich, try to keep it.

We’re Up 15% in a Week